How to plan your own tour: using the Internet and your fans

We just got home from GeekGirlCon, a wonderful convention in Seattle full of the most adorable child cosplay in the world. During that convention we sat on a panel called "Women in Nerd Music" with Molly Lewis, Sammus, Shubzilla and Minn from Thundering Asteroids. It was a really fun and productive hour, with some insights about band names, sexism and the new portmanteau "thermomenerd" (meaning the song used by a band to measure the nerdiness of an audience).The last question in the panel, right under the wire, was "how do you book a tour?" — and we didn't really get to answer it. But folks, I just have SO MUCH TO SAY!Collected below is basically every possible thing I thought of when I thought about tour planning. It may or may not help others, depending on what you want to know. Any advice is most likely to apply to bands with an existing online audience.The post below is not very well organized, and it is not comprehensive, But I think it is a pretty clear reflection of our method for planning tours, with all its benefits and flaws.

We just got home from GeekGirlCon, a wonderful convention in Seattle full of the most adorable child cosplay in the world. During that convention we sat on a panel called "Women in Nerd Music" with Molly Lewis, Sammus, Shubzilla and Minn from Thundering Asteroids. It was a really fun and productive hour, with some insights about band names, sexism and the new portmanteau "thermomenerd" (meaning the song used by a band to measure the nerdiness of an audience).The last question in the panel, right under the wire, was "how do you book a tour?" — and we didn't really get to answer it. But folks, I just have SO MUCH TO SAY!Collected below is basically every possible thing I thought of when I thought about tour planning. It may or may not help others, depending on what you want to know. Any advice is most likely to apply to bands with an existing online audience.The post below is not very well organized, and it is not comprehensive, But I think it is a pretty clear reflection of our method for planning tours, with all its benefits and flaws. WHY WE TOUR: There are lots of bands that don't tour. There are lots of bands that tour more than we do. I think our reasoning for touring comes down to this: we write our music to be performed live. That's where we started: not jamming in a garage, but writing for a weekly open mic. And I agree with many reviewers on the internet—the Doubleclicks are better live. So if we really want to serve our extremely supportive audience, I feel like we should play for them live at least once a year, as much as we can. This reasoning dictates how our venues are chosen: there's a lot of singing along and participation, so we try to play only in places where acoustics allow for jokes and improvisation and talking, and disruptions are minimal (so, not a loud punk bar or outdoor festival). This also dictates which cities we go to: we don't count on tour as our most reliable way of making money (that comes from the internet, crowd-funding and convention shows)—but we don't tour to lose money either, so we keep things reasonable and play places where we know enough people will make it out to be worth our travel time.Since our band started performing as "the Doubleclicks" in 2011, we have toured nationally three times with a sprinkling of additional regional tours (would you like to see our complete archive of show listings? It's extensive!). I consider a "tour" to be a string of shows on consecutive days in different cities—we've done a lot of "appearances" and weekend trips for conventions... but those aren't really "tours." Tours are when we pile into a car, drive all day, play a show, sleep, wake up, and repeat. The longest tour we've done was the "Velociraptour" in 2013: that was 4 weeks and 8,000+ miles. Certainly not impressive by Katy Perry or Megaran standards, but still exhausting. And my voice was gone by the end!We still have no idea what we are doing, but it keeps getting better, and we keep making mistakes to learn from.A note before we begin with the advice: we owe a lot of our tour strategy to people with whom we have played in the past: Paul and Storm, Marian Call, Sarah Donner, and others (thanks, guys!) and we owe even more to the many mistakes and terrible shows we've planned out of our own ignorance. Mistakes! They are the worst!Here we go: HOW THE DOUBLECLICKS PLAN THEIR TOURS1. FIND THE PEOPLE, PART 1. We started touring because people, people who already knew our music, asked us to. Touring is certainly an important way to build a band's audience, to play for new people in their very own cities. HOWEVER, our most successful shows on tours are planned with the help of people who already know who we are. So when we tour, we aren't cold-calling. Before we started touring, we did this:

WHY WE TOUR: There are lots of bands that don't tour. There are lots of bands that tour more than we do. I think our reasoning for touring comes down to this: we write our music to be performed live. That's where we started: not jamming in a garage, but writing for a weekly open mic. And I agree with many reviewers on the internet—the Doubleclicks are better live. So if we really want to serve our extremely supportive audience, I feel like we should play for them live at least once a year, as much as we can. This reasoning dictates how our venues are chosen: there's a lot of singing along and participation, so we try to play only in places where acoustics allow for jokes and improvisation and talking, and disruptions are minimal (so, not a loud punk bar or outdoor festival). This also dictates which cities we go to: we don't count on tour as our most reliable way of making money (that comes from the internet, crowd-funding and convention shows)—but we don't tour to lose money either, so we keep things reasonable and play places where we know enough people will make it out to be worth our travel time.Since our band started performing as "the Doubleclicks" in 2011, we have toured nationally three times with a sprinkling of additional regional tours (would you like to see our complete archive of show listings? It's extensive!). I consider a "tour" to be a string of shows on consecutive days in different cities—we've done a lot of "appearances" and weekend trips for conventions... but those aren't really "tours." Tours are when we pile into a car, drive all day, play a show, sleep, wake up, and repeat. The longest tour we've done was the "Velociraptour" in 2013: that was 4 weeks and 8,000+ miles. Certainly not impressive by Katy Perry or Megaran standards, but still exhausting. And my voice was gone by the end!We still have no idea what we are doing, but it keeps getting better, and we keep making mistakes to learn from.A note before we begin with the advice: we owe a lot of our tour strategy to people with whom we have played in the past: Paul and Storm, Marian Call, Sarah Donner, and others (thanks, guys!) and we owe even more to the many mistakes and terrible shows we've planned out of our own ignorance. Mistakes! They are the worst!Here we go: HOW THE DOUBLECLICKS PLAN THEIR TOURS1. FIND THE PEOPLE, PART 1. We started touring because people, people who already knew our music, asked us to. Touring is certainly an important way to build a band's audience, to play for new people in their very own cities. HOWEVER, our most successful shows on tours are planned with the help of people who already know who we are. So when we tour, we aren't cold-calling. Before we started touring, we did this:

- we wrote and released music that was accessible for free on the Internet.

- we shamelessly plugged this music to people we thought might enjoy it

- we WERE READY: when the audience found us, they had many ways to stay in touch: youtube, twitter, facebook and an email list and website. If people really liked our songs, they could stay in touch, and engage. This is super important. Making a viral music video is one thing, but if those people disappear, it's not going to have any effect on our tour attendance.

- **THE SINGLE MOST VALUABLE THING IN DOUBLECLICKS TOUR PLANNING**: People started to demand, in tweets and comments, that we play in their city. And the most important thing we've ever done is reply to them with this: "sure. where?" That's the important question. At first we would track down and e-mail these fans who were making the demands, asking for advice on venues. Once we had a mailing list, we used it to send targeted "please help us" emails (example here.) And then we created our holy grail: THE MAGICAL FORM OF TOUR PLANNING (link here). In this google form, fans can enter their city, tell us about themselves and their friends, and suggest some of their favorite local venues. And through this form, fans have created for us an Extremely Valuable database: these are the cities in which we have enthusiastic fans, and these are the venues that those fans like to go to: often these places are conveniently located, run by friends, have a built-in community, and/or are pleasant places to hang out. This spreadsheet also includes a list of these fans enthusiastic enough to fill out a form. Who might let us crash on their couch. Who will bring out friends to the show. Gradually, venue owners started filling out this form as well—offering their own game stores. These are the best, because when the owner is excited, the whole organizational structure is working for our show to be great. MOST OF OUR TOUR SHOWS are booked in venues suggested in this form. This saves us tons of time on research and trying to cold-call venues. It saves us the uncertainty of knowing whether we REALLY have fans in Minneapolis or wherever. Sometimes suggestions are unrealistic and some are whiny and some are creepy, but they are mostly SO HELPFUL.

- Here's what I tell myself: YOU NEED LOTS OF HELP FROM YOUR FANS, but you should never feel entitled to this help, and you should always do at least 8x as much work as they do. This is also true of the game store owners, promoters, and other people you work with. All of us are just a small part of each other's job, so it's my responsibility to be diligent in following up with details. It's OUR tour, not theirs. Passive aggression is not an option.

2. DRAW A PICTURE AND MAKE A PLAN. We remember those "COME TO CLEVELAND" tweets, and we have that big spreadsheet created by fans who fill out our form... and then it's time to start planning the tour for real. For a while, we used a service called BatchGeo to actually map our FanBridge e-mail list and see where our fans lived based on zip code. We saw the big concentrations: Midwest, East Coast, Northwest: we could even see which cities and suburbs had the most Doubleclicks listeners (Toronto was a big surprise, and so was Chicago). So once you have the fans, this is the part where you pull up the google maps and the google calendar and ask the questions. How long do you want to tour? What season makes sense for the region? Where do you have fans? Where can you afford to drive? Are you going to fly to the other coast and rent a car? Can you figure out how to borrow a car or make a round-trip rental? Can you bring your own sound setup, so you can play non-conventional venues that do not provide a PA system? Can you anchor your tour with a big corporate, convention or college show to cover some of those big costs? We started very very small with our first headlining tour, with a 5-date tour going from Portland to Vancouver, BC and back. Each time the tours get more ambitious.The hardest part with the map and the calendar is starting. It feels like we have infinite cities and infinite days—with no structure, it's impossible to start. It's helpful to have an "anchor" show or date... for example, we know we need to be in DC when the big venue has a date available, we know we want to be in Boston for the big convention, or we know we want to visit Grandpa on a Sunday. The anchors are annoying because they conflict with the freedom of planning, but they are also necessary. They're a lot like deadlines: nothing gets done without a little bit of structure.Once we have figured out our basics, I start marking my calendar with the master schedule for tour planning: 4-6 months prior to the tour, we tell our fans to get their updated suggestions in via our form (often we do this by posting a map on twitter, maps get people very excited.). 3-4 months prior to to the tour, we'll start booking. A month later we will confirm shows and start working on travel logistics. About 1-2 months out from the tour, promotion stars in earnest, including releasing new videos in which we can put ads for the tour, and printing and mailing posters. We schedule EVERYTHING. Planning! It looks so clean when it's in the future.I sort of love this phase of the tour: the IDEA phase. You put all those cities into a google map and you see what shape your tour's going to take. You have great ideals in your head about how you won't have to drive more than 5 hours a day. You have a perfect schedule for every step of the tour. And then you start booking shows, and everything is ruined.3. FIND THE VENUES AND BOOK THE SHOWS. This is the part of the tour planning that is all about the DATA. We have our spreadsheets about our numbers of local fans, we have a bunch of suggestions, and we have a map. And then?

So once you have the fans, this is the part where you pull up the google maps and the google calendar and ask the questions. How long do you want to tour? What season makes sense for the region? Where do you have fans? Where can you afford to drive? Are you going to fly to the other coast and rent a car? Can you figure out how to borrow a car or make a round-trip rental? Can you bring your own sound setup, so you can play non-conventional venues that do not provide a PA system? Can you anchor your tour with a big corporate, convention or college show to cover some of those big costs? We started very very small with our first headlining tour, with a 5-date tour going from Portland to Vancouver, BC and back. Each time the tours get more ambitious.The hardest part with the map and the calendar is starting. It feels like we have infinite cities and infinite days—with no structure, it's impossible to start. It's helpful to have an "anchor" show or date... for example, we know we need to be in DC when the big venue has a date available, we know we want to be in Boston for the big convention, or we know we want to visit Grandpa on a Sunday. The anchors are annoying because they conflict with the freedom of planning, but they are also necessary. They're a lot like deadlines: nothing gets done without a little bit of structure.Once we have figured out our basics, I start marking my calendar with the master schedule for tour planning: 4-6 months prior to the tour, we tell our fans to get their updated suggestions in via our form (often we do this by posting a map on twitter, maps get people very excited.). 3-4 months prior to to the tour, we'll start booking. A month later we will confirm shows and start working on travel logistics. About 1-2 months out from the tour, promotion stars in earnest, including releasing new videos in which we can put ads for the tour, and printing and mailing posters. We schedule EVERYTHING. Planning! It looks so clean when it's in the future.I sort of love this phase of the tour: the IDEA phase. You put all those cities into a google map and you see what shape your tour's going to take. You have great ideals in your head about how you won't have to drive more than 5 hours a day. You have a perfect schedule for every step of the tour. And then you start booking shows, and everything is ruined.3. FIND THE VENUES AND BOOK THE SHOWS. This is the part of the tour planning that is all about the DATA. We have our spreadsheets about our numbers of local fans, we have a bunch of suggestions, and we have a map. And then?

- Identify the venues: Our tours are gradually growing, and the general shape of successful shows has been this: 2012: house concerts. 2013: game stores. 2014: small venues. 2015: spaceships? From the start, as mentioned, we used our fan's suggestions for places to play. but we also do our research—based on size, people who have played there before, location... and so much more.

- Find venues that are the correct size. Websites like IndieOnTheMove have capacity numbers for lots of venues. We find places that we think we can fill up. We played some stupidly large venues in our early days because of ambitious silliness, and did not make money doing this. Just because we can fill up a 200-seat theater in our hometown doesn't mean we can do the same in Chicago on our first trip. It's better to sell out a tiny show than play for no one, so we err on the small side. We also look at the venue's facebook page to see the layout: is the stage right next to the door or the bar, or is there a nice seating area? Do most people have to stand? Does it look like the proprietor will be disappointed if there is no dancing?

- Look for non-conventional venues. House concerts are great if you're up for the intimacy, and it's free to play. Especially for your first trip to a city, house concerts are great. Once you have a fanbase that extends beyond one group of friends, coffeehouses are nice because there's less pressure to bring out an audience than a full-on venue, and you don't have a booker breathing down your neck about promotion and taking 40% of the ticket sales. We play at a lot of game stores and comic shops because they have a built-in community and usually everyone is really really nice. To find good game stores, we've used the Tabletop Day website, because we know stores that hold Tabletop day events have game rooms and like hosting non-standard events.

- Consider playing a non-conventional venue with a "free/donation" show (The Marian Call technique): this brings in more people, especially for your first trip to a city, and usually the money works out ok if you're good at asking. We find we make an average of $7 per person at a "$5 suggested" show, not counting merch sales.

- Once you've selected a few places to try, find the correct contact at the venue and read all the information. Do they want links to your music or youtube videos? A formatted list of your local draw? Respect their time and follow the rules. Sometimes you have to call people on the phone. This is the worst, but when I do this I remember that there were times when all tours were planned using telephones, and I am grateful to not be living in those horrible times.

- THE BOOKING EMAIL INCLUDES: a personalized salutation, a set of dates, our links, our draw in the area, a personal connection to the venue. I try hard to not oversell us so no one is disappointed or left in the lurch, and you'll see in the game store email I also want to make sure the show is going to meet our minimum requirements before we even start talking. Here are three examples that worked.

200-seat theater in Vienna, VA: 60-seat coffeehouse in Philadelphia:

60-seat coffeehouse in Philadelphia: Game store in Sacramento (this is before we made our bios shorter):

Game store in Sacramento (this is before we made our bios shorter):

- Make your booking e-mail quick and concise. Tell the contact everything he or she wants to know, don't hide anything. Ideally, a fan has referred us to that venue, so we can say something like "Our fans think your venue would be a great fit!" and I think that helps.

- We find that it's best to send these emails in the middle of Monday night so people can turn them around quickly Tuesday morning, but your mileage may vary.

AND THEN:

- Once these e-mails start returning, the real nightmare starts. Both Columbus and Cleveland can host you on Saturday and not Friday. Washington DC can only do the one week that Minneapolis can do. Game stores can never host a show on Friday night because of Magic, and everyone in LA is going to whine about traffic on weeknights. This is still terrible for me. I've started scheduling my e-mails to try to deal with this problem: venues first, then non-traditional businesses, then small, more flexible venues. It still doesn't work great, and I don't find venue bookers to be very sympathetic, but they are working with their own huge spreadsheet, so I try to be nice.

- We juggle this schedule forever. We have to give up on cities sometimes if they don't respond to follow-up emails. Sometimes we discover a small city in between two big ones that has a secret concentration of nerds. And we always neglect to give ourselves enough days off: right now we try to limit ourselves to 7 shows in a row before we need a break.

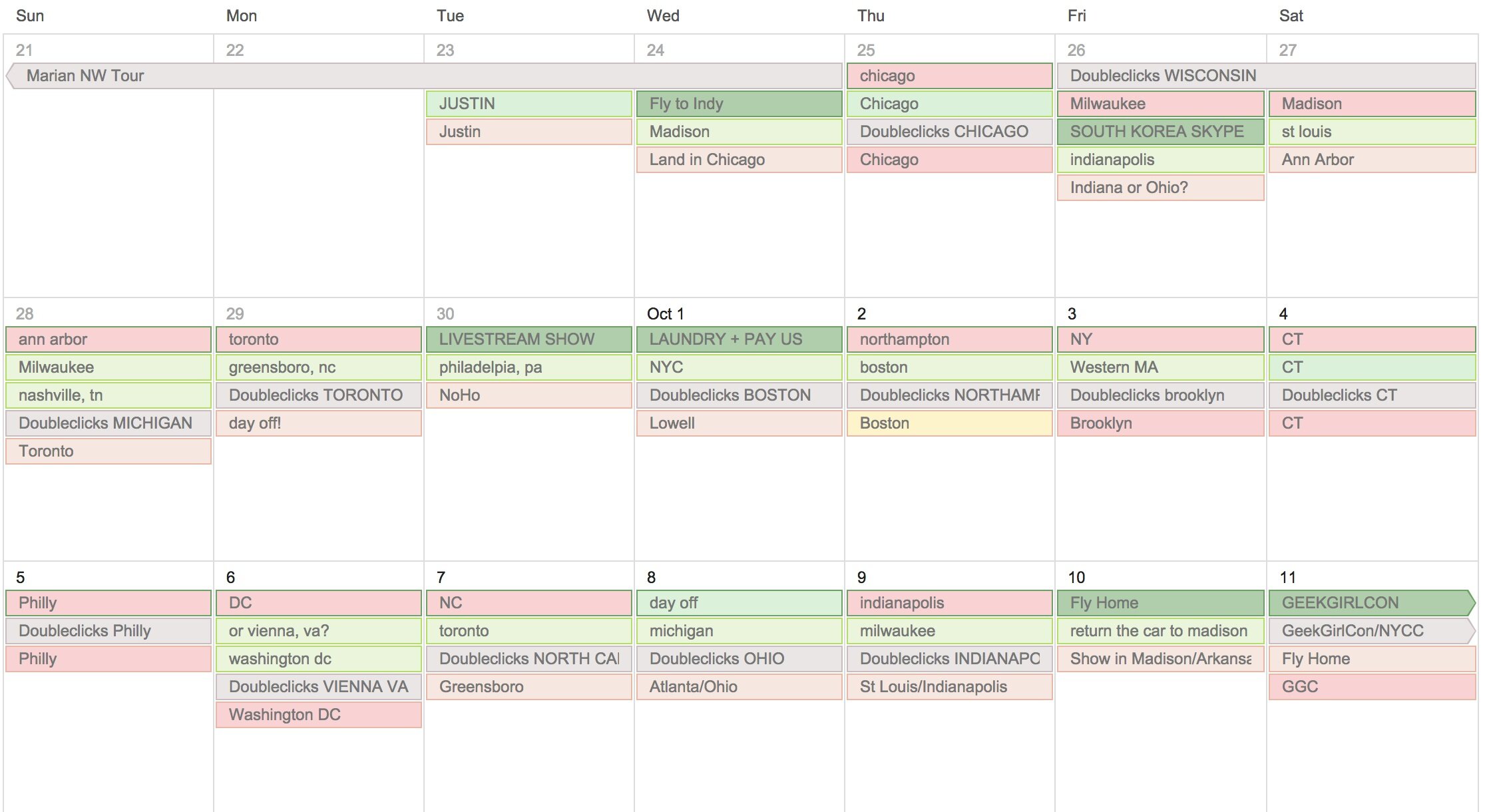

- To give you an idea of the juggling: here is what our calendar looks like—we have 3 different calendars for 3 different possible routes, plus a shared calendar we use so we don't accidentally overlap with our friend Marian Call's tour schedule. It's nuts.

- On openers and sharing shows—our current mindset is this: definitely share shows when you can, with people you LOVE. We are fortunate that we are seldom slapped onto bills with openers we don't know—a practice which can be super frustrating when the person is a sexist or terrible or something, especially when they're taking the money from people YOU brought in. When we can bring in an opener that we know and whose music we love, it is always worth it for the increase in the quality of the show. We've made some mistakes with this in the past, though, particularly early on. Nowadays we will book a show with another act IF: we really like their music and think our audience will too; AND/OR they can help us book a show in a way that will take less work than us doing it ourselves; AND/OR they have a local draw. If none of those things are true, well then we're just being nice to be walked all over... and that happens a surprising amount. These days, because of how much we've been burned, we usually ask openers or co-performers to sign an agreement stating that they will promote the show, in specific ways and a specific number of times. If we're biting off a bigger venue than we can chew ourselves and we're counting on someone else to help out, we need to make it clear to that person that we need their help. Making it part of the contract makes it simple and easy to discuss. We'd love to do more shared tours in the future, but those work best when both acts have their own separate audiences who both would enjoy the other's music, so that the audience is bigger than it would be just for one. Playing shows with our friends is the very greatest thing ever in the world. We do it a lot in Portland and we'd love to do it more around the country, if we could do so while still paying everyone. SOON, I guess!

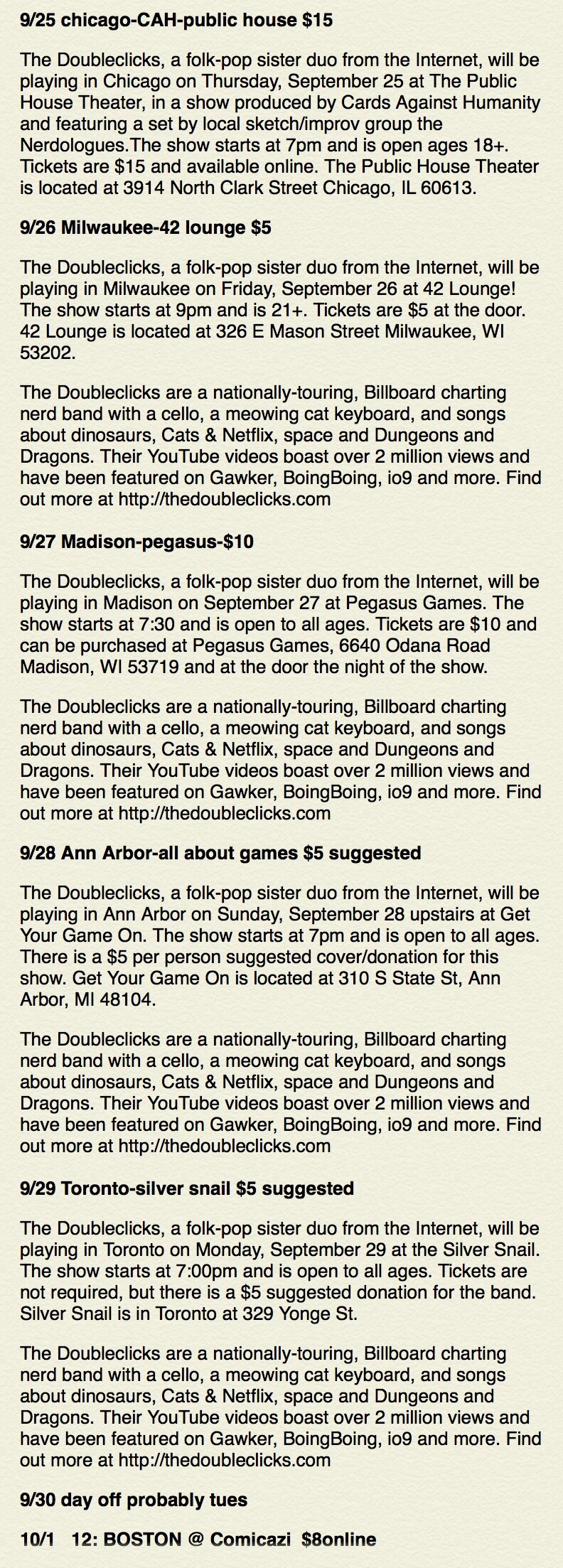

4. NAIL DOWN THE UNKNOWNS. Once the venues have replied (after some pestering, usually), that next step is important. You aren't going to get a lot of back-and-forth with each show: everyone is busy. So it's super important to nail down all the details, the promotion information, your needs and theirs, as early as possible. They may disappear later, when it's two weeks out from the show and you need to know what time doors open. We create an inclusive "confirmation email" that includes (redundantly, sometimes) ALL of the details as we understand them.Every venue gets an "official promo blurb" that serves as an written-in-stone agreement with the final times for door and show, price, age restriction... so if we're not on the same page, everyone knows.

- Spell out your needs: we have FAQ pages on our website for our tech setup, for house concerts, and for game store shows. We learn from our mistakes and incorporate those into our agreements: for example, we have a requirement that "no gaming can happen in the same area where our concert is occurring", and I usually have a game store contact agree to that about 3 times.

- Ask questions and confirm and set a schedule for following up on important details. Don't let this happen to you. "Hey, there's no PA here." "Oh yeah, that was Cody's job." "Where is Cody?" "I don't know, I told him he was in charge of the PA two months ago but I never heard back." See, that's not Cody's fault. You should have checked back in with Cody a month and a half ago. I set reminders for myself to check in on things like this. I also keep an eye on the venue calendars to make sure they don't double-book our night and I send constant confirmation e-mails to openers.

- We always start too late on this, but we have a great big google doc with all the tour information in it (Dammit Liz called this the "tour bible." We used to print it out, but it changes so much that we pretty much keep it digital at this point). This includes where we're playing and the address, load-in and sound check time, the money situation, set lengths, and important contacts. We often paste verbatim agreements into the doc for easy access, so we don't have to pull up emails to prove a point. We also write in our driving distance for the day, where we're sleeping, and then collect all those random tidbits we're sure to forget: it's Kathy in Cleveland's birthday this day, our dad's friend is coming to the show in Fresno, our friend Will wants to grab dinner in Chicago... blah blah blah. People send about a million emails and someday we'll remember to start collecting it early enough to not have a nightmare week pre-tour where I have to search all my e-mails and collect all the information from every city. We also have at least 2 people fact-check the book: on one of our early tours our tour book wasn't accurate some of the time, and even one mistake defeats the whole purpose.

5. FIND THE PEOPLE, PART 2. Press and promotion is something I have a complicated relationship with. Usually, it seems to not make a huge difference how many press releases I send out to the venue's "required press list"... our fans aren't reading newspapers, and most reporters have about 300 different concerts per week that they could be writing about, so it's going to be hard for us to stand out. Below are the things we've learned from our past and from internet "indie musician" blogs (I have more to say on this, but I think things like "how to write a press release" and "how to make a poster" are pretty well covered on many of those indie musician blogs, so I'll keep it to the important lessons).

- First we do our work: we put the events on our website, on songkick, and on facebook. we put out an email blast and tweet and go nuts this way, and we make an easily sharable image and link with all of the important information. And then we go to the press!

- We keep a spreadsheet of everyone who has covered our band in the past, with links to articles. When they do write about/interview us, we encourage our fans to check it out so they see an increase in traffic for those articles and are likely to help out again. We have a comprehensive press page for our own and others' reference, in addition to a few different spreadsheets (promo contacts for tours, for videos, for news, etc). When sending a message to someone who has written about us before, I include a link and a thank-you message about the previous article and give them an update on the band's latest exploits.

- When dealing with print and other old media, I look for reporters who cover similar acts and get their direct contact information. I create a schedule and be courteous of deadlines—if I'm contacting a monthly magazine, I give them 2 months notice. If it's a daily blog, I don't spam them more than a couple weeks in advance.

- I look for local blogs with a smaller but more loyal and targeted audience—these people are more likely to respond than a big mainstream outlet.

- We try to write a press release with a hook (even if the album came out 6 months ago, it's still nice to have an album review as the context for the article). Recently, we've started including a free download of our album in the email.

- For blogs, we suggest ideas for promotions and contests, such as giving away tickets and copies of our CD.

- I send a "Final promo email" to the venues 2 weeks out from the show with a link to our latest youtube video, and often they will put this up on the facebook page with an excited "look who's coming soon!" message. Before I do this, I try to check to see what promo they are doing and thank them for the work they're already doing.

- We ask our fans (particularly those who filled out the form) to e-mail and talk to their friends, and offer rewards for bringing new fans to the show.

- Posters: are they helpful? I don't know. We usually at least send them to the venue, so there's a poster in the window and people know they are in the right place. Generally, I think posters "in the wild" mostly just help if people already know your band by name, and at the beginning this isn't as much the case and the investment isn't really worth it. Better to spend that time making a new video, writing something for the e-mail newsletter, or commissioning an image for the web.

But really, this is what works:

- We promote the heck out of our tour to people who already follow us. We Facebook and tweet EACH show on the tour on a different day. About a month before the tour and again a week in advance, I will designate each day to a different city, and promote it on social media: a tweet @-mentioning the venue and local opener, a targeted Facebook promoted post with a picture. We use YouTube videos (people love new music!) as a place to put in our own tour advertisements, either at the beginning or end. It can feel like we're drowning people in promotion, but no one has complained yet. What people do complain about is how we "never come to Cleveland"—a week after we just did a show there. (Sorry for all the crap, Cleveland.)

6. PUT ON A SHOW. Here are the things we've learned about the actual "tour" parts of tour:

- Bring enough clothes and merch. Think about making a tour t-shirt! Ship stuff ahead of time! We never plan well enough to do this.

- Be nice to every person you meet every day in every part of the show. It takes only one tiny interaction for the phrase "oh yeah, I hear they are jerks" to proliferate. And it doesn't matter whether this is true.

- Be honest and open with the people you're touring with. Give each other space and don't take it personally when people need time off.

- Give CDs to the sound guy and remember his name. (He's usually the coolest guy at the show anyway).

- Keep track of your setlists so you know what stuff this city has and hasn't seen (we have a folder on our computer).

- Write down your promo/merch plugs on the setlist so you don't forget to make people join your mailing list.

- Remember: you don't have time or the obligation to be a tourist. You aren't traveling, you're touring. So take breaks and don't schedule crazy trips (but take them when you have the time and energy!)

- Use this service to get people to join your mailing list on their cell phones during the show: skaflash.com

- Take pictures with your audience so you can remember their beautiful faces.

- When tour feels hard, remember how lucky you are that this is your job, and shut up. When it's easy, take pictures and tweet how happy you are.

- Your audience can tell when you are having a good time. So have a good time. And they will have a good time. This is not optional.

- Nothing solves tour stress like other people's cats.

7. REGROUP, LEARN, TAKE BREAKS, and DO IT ALL AGAIN.

- Woo!

Touring is the best. We genuinely love it. It's full of logistical nightmares, but every one is worth it.If you have any specific questions, please leave them in the comments or e-mail me at angela *at* thedoubleclicks.com, and I'll answer as time permits.EDIT: if you are a fan and want to offer a venue or a place to stay, please don't e-mail us, go fill out our form! http://bit.ly/suggestacity

The Doubleclicks are made possible by support from their listeners. If you'd like to support, please consider buying an album or some songs for the price of "pay-what-you-want" on Bandcamp.